Image source linked here.

For the purposes of this post, I’ll be using “moral” / “morality” interchangeably with “ethical” / “ethics.” This does not necessarily have any bearing on my usage of those terms in any of my other posts, nor does it necessarily not have any bearing on my usage of those terms in any of my other posts.

Part 0: What am I doing here?

The purpose of this post is not to teach you about Nietzsche, or Kant, or Stirner, or even perhaps about ethics at all. Rather, the purpose of this post is to draw out the system by which I try and make my decisions in life, particularly as they come to effect or involve other people. If you are incidentally to glean something from this post about moral philosophy, then more power/knowledge to you. I will do my best to write in a way that is accessible to someone who has zero knowledge of any philosophy, but I think it is common occurrence that even when trying to compensate for it, experts (if I may be so brash as to label myself as such) “wildly overestimate the average person’s familiarity with their field.”

Part 1: Too many hammers, too few nails

I generally tend to approach concepts of morality from a Nietzschean or Foucauldian perspective: genealogical analysis for the effect of demonstrating social constructedness and historical relativity (masterfully applied to philosophy of disability here by friend of the blog, Biopolitical Philosophy). Or, put more simply, “‘X’ or ‘Y’ hasn’t always been this way, and thus it doesn’t have to be this way, nor does it have to continue to be this way.” And put once more, because why not, morality is an outcome of sociohistorical power relations, and so there is little inherent or “natural” reason to bend the knee to the demands of morality, especially when said demands run contrary to our perceived best interest. If you don’t understand this, then read Nietzsche’s “On the Genealogy of Morality” or Max Stirner‘s “Ego and its Own” or something. If you don’t agree with this, then… well, the point of this is to not convince you of anything anyway.

Although I’m highly sympathetic to these aforementioned arguments, and I think that they’re largely “correct,” to the extent that such things can be correct, they do not tend to lend themselves to a fulfilling life. At least, not in my personal experience. Max Stirner’s work may have spawned some fun memes, but stealing from Walmart and squatting in people’s houses doesn’t get one far in this society that we find ourselves in.

An aside: yes, I know that Max Stirner’s Egoism is not the exact same as Nietzscheanism. But as far as I can be convinced, they’re effectively the same in practice. Especially anarchist practice. At a minimum, their similarities are noteworthy (maybe).

Regardless: I often found myself in situations in which I was faced with the question, “what should I do?” And, the view that “I should do what I want” did not elucidate much. What do I want? What should I want? What is valuable in life? How should I prioritize multiple competing self-interests? I love drugs and I also am an addict. Do I shoot up or not?

An aside: does anyone else find Nietzsche’s “eternal recurrence” an interesting lens to view cycles of addiction and relapse through?

A Stirnerist egoism doesn’t provide me many answers to these questions (do they provide you answers to those questions? maybe! let me know!). And so, in my ways, I am once more driven to discover/develop a system by which to make decisions in my life. One might say, an ethical system.

Part 2: In search of an ethics

Of the famous philosophy thought experiments, Immanuel Kant‘s “Murderer at the Door” scenario… might be one of them?

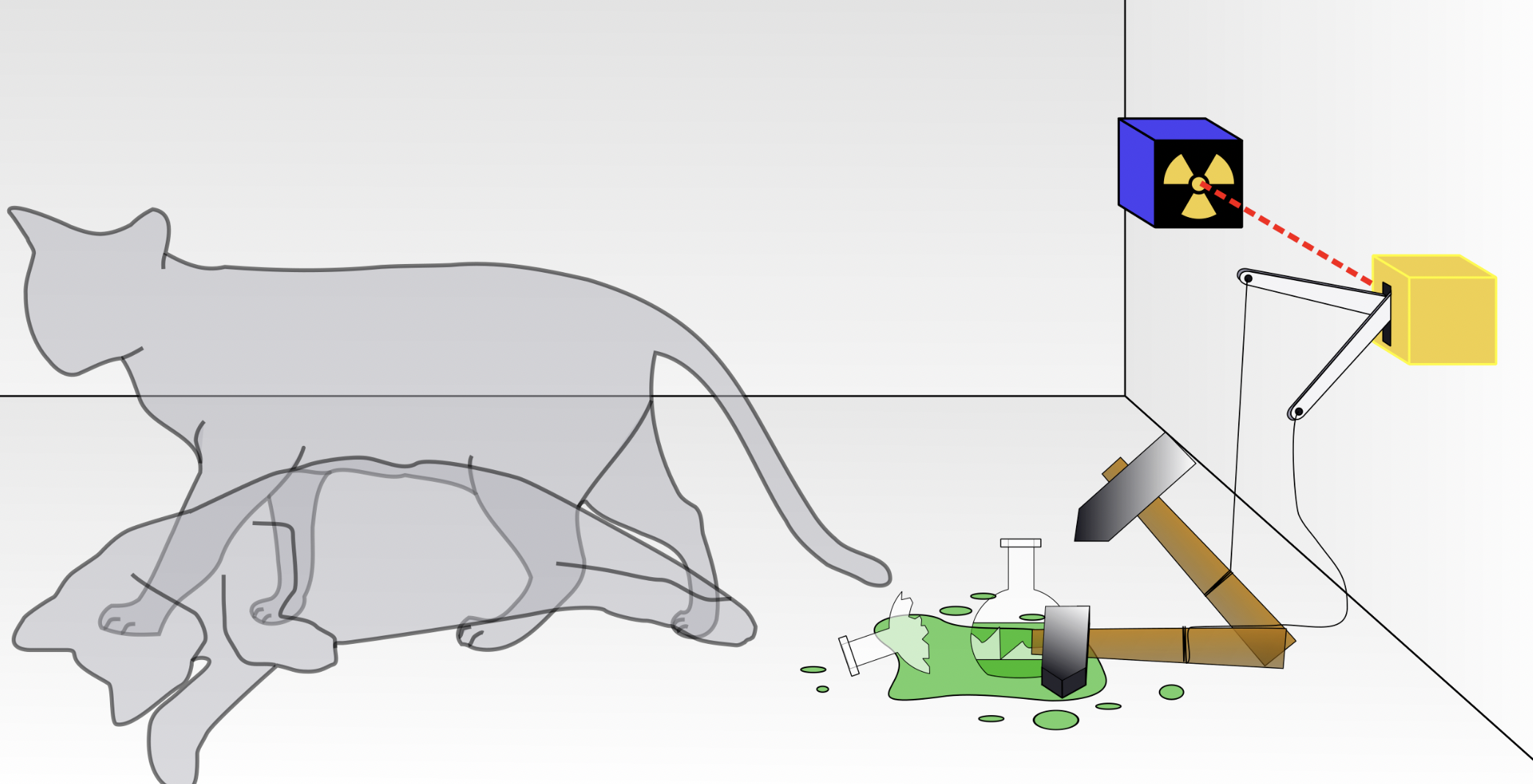

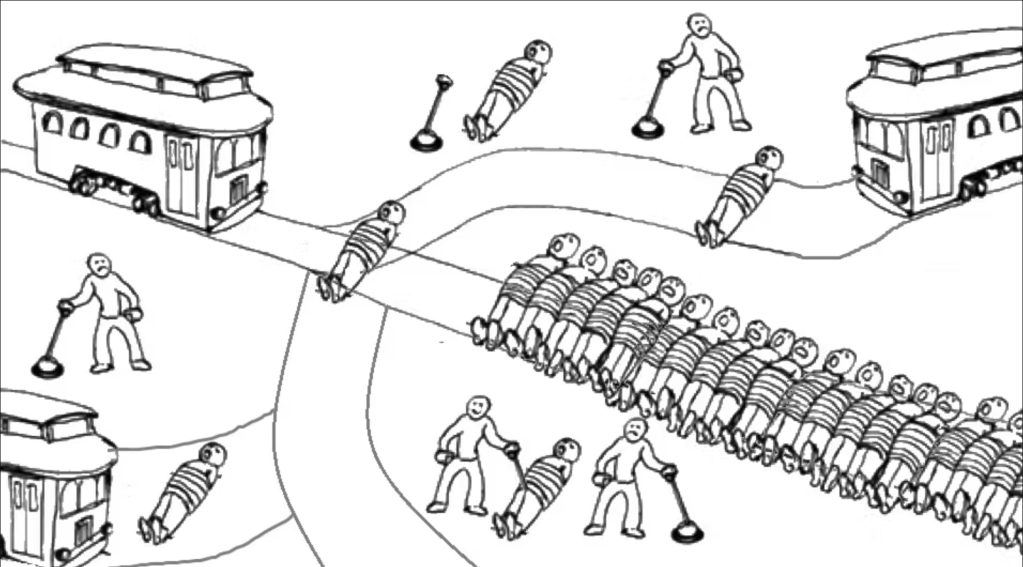

an aside: the most famous, if I were to hazard (pun intended) a guess, would likely be the trolley problem. Please do not interpret my linking of a clip from The Good Place as my endorsement of The Good Place. I am, notably, largely unimpressed, unamused, and uninspired by most of the show.

Actually, as I write the above aside, I find myself thinking that Kant’s “Murderer at the Door” and the trolley problem are perhaps two different ways of drawing out the same problem: having to chose between deontology and consequentialism.

In the trolley problem, one must decide between letting the trolley run its course, killing five people, or intervening to change the tracks, actively diverting the trolley to kill one person instead. Utilitarian consequentialism tells us that we should make decisions that foster maximum happiness: in this case, the death of five people leads to less total happiness than the death of one person (assuming, of course, that death is unhappy). And so, per a utilitarian consequentialism, we should divert the trolley, resulting in the most minimal (some might say, “minimum”) decrease in total happiness. However, per a deontological ethics, one that has as a maxim “never kill someone,” then to divert the trolley is to engage in the act of killing someone, while failing to divert the trolley means that one does not engage in the act of killing, as inaction is not action (perhaps).

Alternatively, in the “Murderer at the Door” scenario, one must make the decision between telling the truth to the murderer, resulting in the death of one’s friend, or lie to the murderer, resulting in the friend’s survival (but, of course, telling a lie in the process). I think it is very common to have an intuitively utilitarian response to this scenario: lie, and save your friend. After all, this person is a murderer! Are not all deceptions permissible in such dire straits? However, to Kant, to lie in this scenario is to inhibit the murderer from rationally choosing their own ends: you have incapacitated their reason (a deontologically forbidden action)! And, I guess, here is where I do need to explicate some about Kantianism, in order to understand what is truly so wrong with the incapacitation of another’s rational faculties. As much as I intended to do this post with no learns, we must nonetheless tread into such waters.

I don’t want to dive too deep (to continue the water metaphor) into Kantian psychology, and so for simplicity’s sake I will simply state some conclusions, and leave out the argumentation that leads to those conclusions.

an aside: I can leave out all this argumentation because, as mentioned previously, my goal is not to convince you of anything. I do not seek to demonstrate the validity or veracity of Kant’s moral philosophy.

Kant understands humans as being fundamentally rational beings. We humans are given many incentives from our psychology, our environment, and our moral thoughts — as rational beings, we choose which, if any, of these incentives, or “ends,” to pursue. Every rational being considers their rational nature as an end in and of itself. For Kant, this, in conjunction with lots of other claims, gives rise to the moral law, the formula of humanity; “so act that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means.”

What does this mean? We must never take an action that uses an individual’s rationality as a means to an end. We must always act so that we maximize capacity for rational thought. We must encounter each other’s rational nature as a source of unconditional value, and so respect each other’s actions and ends as being rationally-determined.

And this is why lying to the murderer at the door is wrong, per Kant: to do so is to use their rationality as a means to an end —— in this case, the end is the survival of our hunted friend.

To view another as rationally-determined requires that we hold them responsible for their actions and ends. If we do not hold someone responsible, then there is a sense in which we do not view them or their actions as rationally-determined. This is where, in my opinion, Kant connects in such a satisfying manner to the work of P.F. Strawson: on the connection between responsibility, rationality, and autonomy. We swim further in…

Per Strawson, we hold people responsible out of our demand for goodwill or regard from those who we are in relationships with. In this way, holding someone responsible relies on the view of them as acting from intention, and having a capacity such that they can be reasoned with.

Let us draw out exactly what this means via the following scenario: your friend walks directly up to you, looks you in eye, and with great conviction and malice steps hard on your toes. Ouch! You would likely be upset with this individual in such a scenario. You might yell and curse at them, or be saddened about the state of your relationship with them, or even seek legal recourse, if you’re truly a narc. Any of these reactions are a form of holding your friend (or, at this point, potentially ex-friend) responsible for their action (stepping on your toesies), which you do because their action was one that was rationally willed. And, further, you believe that your friend will in some way be responsive to your reaction, and potentially even learn something from it. This is what P.F. Strawson refers to as the reactive attitude:

“…the range of reactive feelings and attitudes which belong to involvement or participation with others in inter-personal human relationships… include resentment, gratitude, forgiveness, anger, or the sort of love which two adults can sometimes be said to feel reciprocally, for each other…”

To make this abundantly clear, we can consider an alternative scenario: your friend, whom you know struggles with great spells and bouts of sleepwalking, walks directly up to you at 3am, looks you in eye…

an aside: do sleepwalkers have their eyes open whilst sleepwalking? we shall assume they do for the sake of the hypothetical. not that it is relevant at all; I merely wish to maintain hypothetical symmetry.

…and steps hard on your toes. Ouch! Although the material harm is the same as in the first scenario, in this instance you would likely not be upset with your friend. Why? Because they did not rationally will their action! And so what sense would it make to be upset with them, or in any way hold them accountable! No, rather, we treat our sleepwalking friend as we would treat a hurricane, or a tree falling on our car, or an alligator —— something to be managed, solved, or otherwise dealt with. This is what P.F. Strawson refers to as the objective attitude:

“To adopt the objective attitude to another human being is to see him, perhaps, as an object of social policy; as a subject for what, in a wide range of sense, might be called treatment; as something certainly to be taken account, perhaps precautionary account, of; to be managed or handled or cured or trained; perhaps simply to be avoided, though this gerundive is not peculiar to cases of objectivity of attitude.”

The claim that I am attempting to make is that there is a certain way of treating one another that both follows from, and thus implies, an assumption of rationality and reasonableness. Now, what I do not want to argue is that rationality and reasonableness are good, or even existent (in fact, in an eventually forthcoming post, I will likely argue that rationality is the root of much bad in the world). Ultimately, this past section, “Part 2,” has detailed the general contours of the system that I try to live and make decisions by. A system in which I honor individuals as ends-in-and-of-themselves, and thus treat them as rational and reasonable beings —— when that means thanking them for helping me, yes, but also when that means rebuking them for stepping on my toes. No using people. Yes holding people accountable (both good and bad).

Part 3: The purpose of a system is what it does

To fully recap: Nietzschean and Foucauldian critiques of morality are by-and-large “correct,” however minimally fruitful in telling me how to live life. An appropriation of Kant’s “formula of humanity” without all the surrounding argumentation, combined with what P.F. Strawson terms “reactive attitudes,” provides us with a way of making decisions (what one might refer to as an “ethical system”).

Now, this of course begs the question: why should I, or perhaps even we, use this particular system, as opposed to any other option? A marvelous question indeed! And one I must take seriously if I am to, as I set out to do, demonstrate the ways in which I have employed an ethical system to a greater degree of life-satisfaction and quelled-conundrums than I was deriving from a Stirnerist egoism.

I will start with perhaps the weakest argument in favor of this so-called system: intuition. I do believe that there is, in some sense, an extent to which this reactive treatment of one another is intuitive to us. Consider the sleepwalking example: I did not have to deeply argue for the application of objective attitudes in that scenario. However, I’m not sure such justification withstands a Nietzschean scrutiny (must it?), and so we shall swiftly disembark to our next argument.

Perhaps because I am still at my core deeply sympathetic to Stirnerist arguments of egoism, I find the ego-satisfying aspects of this Kantian appropriation to be attractive. It immensely satisfies my ego to be in deep relationships and community with other people (other “egos,” as Stirner might say). And, to treat one another as agential beings (not to be confused with “agenital” beings) tends to have the effect of fostering these deep relationships and community.

Plutarch wrote on friends and flatterers —— the latter, an “enemy of the truth,” who feigns agreeableness. The former “seeks to profit you by speaking truth.” To never use another’s rationality as a means to an end relies upon truth-telling, as evidenced by the axe-murderer-at-the-door hypothetical. And to engage another with reactive attitudes is to truthfully respond to that person —— you let them know how their actions made you think and feel (grateful, resentful, etc.), regardless of the happiness outcome. To hold someone accountable is to be truthful to them and yourself. Temporarily putting aside the deeper question of Truth, we can understand that our ethical system does fulfill this notion of friendship, and not flattery. Or at least, I can understand it. Maybe you can’t. Hopefully you can, though.

Well, fulfills this notion of friendship, except for the temporarily postponed question of Truth, which merits a return. And, also, the unmentioned question of, if we are doing this for the satiation of our ego, then can we really say that our truth-telling is at the same time for the profit of our friends, as is the definition of Plutarch’s “friend?” Perhaps these questions are where I am a failed Nietzschean. I think that I believe both that, 1. Truth is relative, socially constructed, and likely non-existent and thus never-attainable, and also nonetheless that, 2. Truth is something we should always aim towards.

What does that actually mean? Maybe this is where the threads of this post unravel. Maybe this is where there are endless questions, and never enough answers. Or, perhaps (here is my way out of these bottomless pits) this reveals the two possible ways that I might explain the merits of this ethical system: if you value relationships with others, then this ethical system is conducive to those ends. Or, if you value Truth and the pursuit thereof, then this system is also conducive to those ends. And, either way, this system answers questions that egoism can’t (in my opinion), and answers these questions in a more life-satisfying way (in my opinion). At a bare minimum, stow these thoughts away as another tool in your ethical toolbox.

These thoughts will be returned to and expanded upon in my forthcoming analysis of time travel visual media.

Leave a comment