In lieu of a more precise source, image credits go to here. If you know the name of the illustrator please contact me so I can put their name here.

————————

Personal Disclaimer: I am unhappy with the extent to which I have staked this argument on originalist interpretations of the 4th Amendment, references to founder’s intent (whatever that means), and the opinions of the late Justice Scalia. Please do not take this argumentation to reflect my broader views of law, government, or the American origin story.

————————

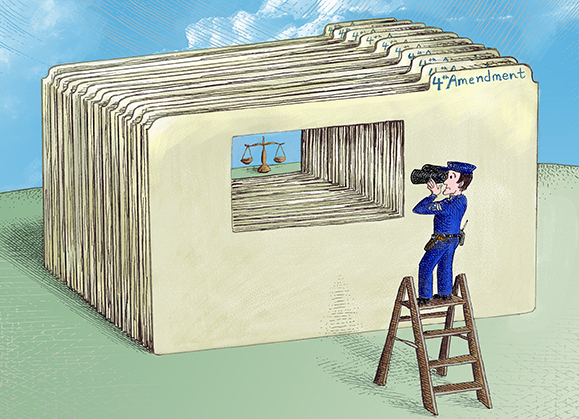

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

Here is how the 4th Amendment functions, in its most basic form: When the government wants to legally look (“searches”) and/or take (“seizures”) you or your stuff (“persons, houses, papers, and effects”), they must first get a warrant from a judge (“and no Warrants shall issue”), based on a some sort of meaningful information (“but upon probable cause”) that searching and/or seizing you and/or your stuff will provide evidence of criminal activity.

In its plain text, the protections of the 4th Amendment apply to four things: persons, houses, papers, effects. It is important to note: these are things. material things. property.

An aside: Now, I am critical of concepts such as private property, natural “God-given” rights, and many other related concepts. However, because this essay will be about the deleterious development of 4th Amendment jurisprudence, those critiques will have to be put to the side. For now, at least. While I may (or may not) be a fan of the ideological underpinnings of the plain-text (or, “originalist”) interpretation of the 4th Amendment, I will say that there are better and worse possibilities for our law, and the current reality of 4th Amendment jurisprudence is, in my opinion, worse than the plain-text 4th Amendment. And so I can say that:

- the current “version” of the 4th Amendment is worse than the “originalist” “version” of the 4th Amendment, and that also

- the originalist version of the 4th Amendment is not necessarily ideal.

This essay will be about that first claim, and not the second claim.

An un-aside: As told by the late (and maybe not-so-great) former Justice Antonin Scalia in his dissenting opinion in Maryland v. King (1980), the reason for the 4th Amendment goes something like this (what follows is not a direct quote):

In the years leading up to the American Revolutionary War, general warrants were issued by the courts of Great Britain. These warrants authorized British officers to conduct searches unlimited in both scope and application. During the ratification debates, Antifederalists argued that the new Constitution would fail to protect the public from similar arbitrary searches and seizures. James Madison responded with a draft of what would eventually become the Fourth Amendment, writing broadly to defend the citizenry from any sort of unreasonable search or seizure by the government.

Persons, houses, papers, effects.

Olmstead v. US (1928)

Olmstead v. US (1928) presented the issue to the Supreme Court, “whether wiretapping of private telephone conversations, conducted by federal agents without a warrant, constitutes a violation of the 4th Amendment.” During Prohibition, our friend Roy Olmstead managed a bootlegging operation. He was arrested and charged for conspiracy to violate the National Prohibition Act. During his trial, evidence was introduced that supported these charges. However, as the issue suggests, this evidence was the result of many months of warrantless wiretapping by federal agents. Recalling the text of the 4th Amendment,

“the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue…”

What this ultimately means is that, if the government has obtained a warrant by following proper procedure, then they are allowed to search and seize your persons, houses, papers, and effects. In Olmstead, the federal agents did not have a warrant. Now, if what they were search-and-seizing did not count as a person, house, paper, or effect, then they did not need a warrant, and thus the search-and-seizure was all well and good. But, if our friend Olmstead’s telephone conversations did count as a person, house, paper, or effect, then the agents did need a warrant, and thus violated Olmstead’s 4th Amendment rights.

In short, the Supreme Court held that no, this did not constitute a violation of Olmstead’s 4th Amendment rights. That, essentially, all the federal agents did was utilize their capacity for hearing (albeit aided by an instrument), and no material thing was actually searched or seized.

For the purposes of this essay, these are the key takeaways from Olmstead v. US: that

- Olmstead’s telephone conversations did not count as person, house, paper, nor effect, and therefore

- the warrantless search and seizure of Olmstead’s telephone conversations did not violate his 4th Amendment rights.

Katz v. US (1967)

Oh Katz… the bane of my existence. The namesake of this essay. A case that singlehandedly changed the course of 4th Amendment jurisprudence. One of the most pernicious cases that I can think of (as opposed to the obviously horrendous cases of Dred Scott, Korematsu, and the like…).

Katz follows a relatively similar issue and fact pattern to Olmstead: Charles Katz frequently used a telephone booth near his apartment to transfer sports betting information across state lines, which is apparently a crime. The FBI bugged this telephone booth without first attaining a warrant, and then used the recordings to prosecute Katz. Katz called for this evidence to be thrown out as it was (allegedely) obtained through the violation of his 4th Amendment rights. The issue is as it was in Olmstead: whether warrantless government surveillance of telephone conversations constitutes a violation of the 4th Amendment. And to the Supreme Court Katz went!

Now look, I could go into detail here about the caselaw that had developed between Olmstead and Katz (such as Goldman and Silverman), and discuss the fine contours of how trespass interpretations of the 4th Amendment intersected with different methods of wiretapping, and the contemporaneous development of implied privacy rights within the Constitution, but the fact of the matter is that you are not my professor, and this essay is not for a grade. Maybe one day I will come back to this to fill out some of the relevant precedential details, but that day is not today. For now, all you need to know is that there were cases between Olmstead and Katz that lead the Court to reconsider the issue of warrantless government wiretapping.

In Katz, the Supreme Court overturned their prior decision in Olmstead. The Court held that warrantless government wiretapping does constitute a violation of one’s 4th Amendment Rights. However, the Court did not find that Katz’s telephone constituted “persons, houses, papers, or effects”, and thus entitled to 4th Amendment protections. Instead, the Court held that the 4th Amendment, in addition to protecting persons, houses, papers, and effects, also protects wherever a person holds a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” Because we generally and reasonably expect the conversations we have over telephone to be private communications, they are protected by the 4th Amendment.

Please at this time recall the text of the 4th Amendment. If you recall accurately, you will find that no where in the 4th Amendment (or in fact, in the entire Constitution) does the word “privacy” appear. And most certainly not the term “reasonable expectation of privacy.” But, because of the way precedent works, following the decision in Katz, the 4th Amendment might as well have been errata’d to read, “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, and also anywhere they have a reasonable expectation of privacy, against unreasonable searches and seizures…”

And this brings us to the meat of the issue: with Katz v. US, the 4th Amendment goes from protecting specifically and merely property (persons, houses, papers, and effects), to also protecting privacy. Yes, this has the added benefit of making the 4th Amendment protect our telephone conversations from government wiretapping… or does it?

The Third-Party Doctrine

Consider: you’re have a casual conversation with Judith about your plans for the weekend. later in the day, a mutual friend of you and Judith says, “oh, Judy mentioned you’re going to the movies this weekend. what’re you seeing?” The reasonable person would, at least according to the Supreme Court, not feel that their privacy has been violated. When we talk to people, the general custom is that unless we heavily preface our conversation with swears to secrecy, or the topic of conversation is highly taboo, we can’t reasonably expect that our interlocutor will take what we discuss to the grave. Or, at a minimum, we are generally aware that our interlocutors could always repeat to another what we have told them. And so: do we truly have a reasonable expectation of privacy around our conversations with another?

Consider further: in the back (or maybe, for some of us, the front) of our heads, we all know that the history of our banking transactions are recorded and maintained, and stored somewhere digitally or physically at our bank. It follows from this, then, that any bank employee with a certain level of clearance would be able to peruse our transaction history. Do we reasonably expect these records to be private?

Once more: simply put, when you send a text message to a friend, your phone company (AT&T, Verizon, whatever) converts your text into a data package, sends it to a phone tower, where it is then sent to another phone tower, so on and so forth, til it gets to your friend’s phone company, and then your friend’s phone. I think that’s how it works at least, but what do I know. Regardless, I think/hope that we all know that texting is not as straightforward as handing a note directly to a friend. Rather, it is more akin to passing a note to a person, who then passes it to another person, to another person, to another person, and then to your friend. Any and all of those people could read the note, and they all know from whom the note is originally coming, and to whom it is ultimately going. How much can we reasonably expect this note to be private? And, this all is just as true of our phone calls as it is our texts.

This is not hypothetic drivel. These are real cases that went to the Supreme Court and were determined to not warrant 4th Amendment protections because they concerned things that we do not attach with a reasonable expectation of privacy. U.S. v. White (1971), U.S. v. Miller (1976), and Smith v. Maryland (1979), respectively.

In White, the Supreme Court responded to the question of whether an individual’s expectation of privacy in information they voluntarily shared with a third party was justified when the third party was secretly carrying an electronic recording device, which was later used as evidence against White. The court held that because an individual is not protected when an accomplice becomes a police agent, an individual should not be protected when that accomplice records a conversation, to later be provided as evidence against White. Therefore, White did not have a reasonable expectation of privacy, and the information conveyed was not protected by the Fourth Amendment.

Five years later, U.S. v. Miller presented to the Supreme Court the issue of whether the contents of an individual’s bank records, which were voluntarily provided to a bank in the ordinary course of business, were protected by the Fourth Amendment. As in White, the Supreme Court applied Katz to the third party doctrine, holding that the documents were not protected as they were not regarded with a legitimate, reasonable expectation of privacy. Apparently, by simply participating in the economic realm, for which a bank account is necessary, an individual waives the protections afforded to them by the Fourth Amendment.

In Smith v. Maryland, the Supreme Court maintained their position that information voluntarily shared with a third party is not afforded a reasonable expectation of privacy. The court held that the use of a pen register to record the phone numbers dialed by an individual does not constitute a search within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. The court reasoned that an individual is typically aware that the dialed numbers are conveyed to a phone company, which is likely to record the information for business purposes. When an individual voluntarily conveys phone numbers to a phone company, they assume the risk that the company would reveal the information to the government. Therefore, as an individual does not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the phone numbers they call, the numbers are not protected by the Fourth Amendment.

Analysis

These cases reveal the troubling nature of Katz and its effect on the third party doctrine. As technological capabilities advance, their role in society becomes increasingly pervasive. Due to this precedent, individuals must choose between either engagement in the social sphere, or the security of their Fourth Amendment rights. In recent years, the Supreme Court has refused to extend the third party doctrine to issues involving an individual’s cell phone location data. This potentially signifies a reconsideration of the scope of the doctrine. However, it fails to address the larger, underlying problem: Katz itself, and the accompanying “reasonable expectation of privacy” test.

Under Katz, the Fourth Amendment protects an individual’s privacy, even though the word “privacy” does not appear even once in the Constitution, let alone the Fourth Amendment. This is the central flaw of Katz. It claims that the Fourth Amendment protects “people, not places,” (Katz, 389 U.S. at 351), affording constitutional protections to areas that an individual reasonably believes is private.

This is contrary to both the framer’s intent and the language of the Fourth Amendment.

The Fourth Amendment was drafted in response to the issuance of general warrants by the British monarchy. These warrants violated the colonialists’ security in property, an ideal that the framers held in high regard. At the time, John Locke’s conceptualization of property rights “permeated the 18th-century political scene in America.”

Furthermore, a reading of the plain text of the Fourth Amendment clearly shows its property-based protections: “persons, houses, papers, and effects.” The privacy rights alluded to in Katz are merely a consequence of these property protections. Katz muddles the property rights guaranteed by the Fourth Amendment with one’s purpose for exercising those rights. In fact, the majority opinion in Katz readily admits that “the Fourth Amendment cannot be translated into a general constitutional ‘right to privacy,’” and “often has nothing to do with privacy at all.” The lack of justification for the Katz test is mirrored in its seemingly arbitrary application and meaning.

An individual’s expectation of privacy is “reasonable” if society is willing to recognize it as such. However, society’s concept of privacy is informed by the Supreme Court. This circular interpretation is pointed out by the late Justice Scalia in Minnesota v. Carter, where he wrote that “the expectations of privacy… that society is prepared to recognize as ‘reasonable,’ bear an uncanny resemblance to those expectations of privacy that this Court considers reasonable.” In addition, it is entirely possible for an individual to have a reasonable expectation of privacy in someone else’s property [citation needed].

And look, I don’t super believe in appeals to the framer’s intent as carrying the weight of the sanctified word of God. However, that doesn’t mean that Rian Johnson’s Star Wars movie wasn’t terrible. To vaguely gesture in Ronald Dworkin’s direction, law is a book that is constantly being written, passed from author to author. And the authors of Katz were on a completely different wavelength than the authors of the 4th Amendment, and I think that this disconnect has rendered the 4th Amendment largely useless in the technological age. And I think that a more robust property-based interpretation would be significantly more better about keeping the government out of our shit without the proper warrants.

If the legislature wrote law that gave us property claims to the data that is created as a byproduct of our individual existence and actions, then theoretically it would be protected by a property-based interpretation of the 4th Amendment. Of course, that requires the legislative branch to curbstomp the power of the executive branch, so, I’m not getting my hopes up anytime soon. That sure would be nice though. Especially the part about the executive branch getting curbstomped…

The Fourth Amendment interpretation proposed under Katz v. United States remains unsubstantiated in both its justification and its application. The “reasonable expectation of privacy test” has no support in history, precedent, or the Constitution. Regardless, it has provided the framework for significant caselaw that greatly restricts individuals’ ability to secure their Fourth Amendment rights against the rapid integration of technology in society. If the courts continue in their application of Katz, its subversion of property rights may very well lead to the very thing the Fourth Amendment was originally designed to prevent: subjugation of the citizenry to arbitrary searches and seizures.

This will not be my last post about government surveillance…

Leave a comment